I was forwarded an article last week about the suicide bomb attack that killed four of the kids from the non-profit skate charity ‘Skateistan’ in Kabul, Afghanistan. A heartbreaking read for anyone but it particularly hit me hard as I had been with those kids just three months ago.

In early June this year, I found myself sitting in the back of a jeep tearing straight down the middle of a two-lane desert road in the Balkh province, Northern Afghanistan, sirens blazing, sandwiched between two burly soldiers holding Kalashnikovs. The other motorists were being forced off the road to let us pass as we pursued our RPG and machine gun armed police escort ahead. As we cruised by UN troops en-route to Mazar-e-Sharif, I wondered what they would think if they could see the skateboard that was tucked between my knees. The two luxury SUVs with tinted windows in close convoy behind us belonged to the Governor Atta Muhammad Noor, and carried my friends from Europe, the States and Russia. I’m a 25 year-old skateboarder from middle England wondering – ‘What am I doing here?’

A week before arriving in Afghanistan, I had absolutely no idea that I would ever go. While on a visualtraveling trip from Beijing to Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, we found ourselves in an awkward moment in Uzbekistan as we got an email from the embassy of Turkmenistan, informing us that our visa applications had all been denied as they had researched us on the Internet and were worried about professional photography and filmmaking. Our guide’s friend was Afghan and suggested that we ended our trip in Afghanistan. He told us that his father worked for the government and could help us and arrange bodyguards. Weighing up our options and fuelled by our hunger for adventure, we decided to take our chances and make one last stop on our trip.

The first few days were spent touring around some of the most ancient Islamic monuments on the planet, playing with firearms and trying to skateboard. Most of the locals had probably never seen a skateboard before, so we drew a huge crowd wherever we went. The reactions were mostly positive. One onlooker told me “We have seen so much war in our country. It’s great to see something that looks so fun”. The Taliban even banned flying kites during their rule from 1996 – 2001 so it’s easy to imagine the interest in a group of foreigners practicing a very American sport just of fun in their rugged streets, but we were also warned not to stay in one place for more than 15 minutes. Even the guards seemed to get pretty nervous as we attracted too much attention and try to herd us back into the cars. Everything seemed safe but there was always a nagging feeling that something could happen. We were also quickly ushered away while visiting the blue mosque in Mazar-e-Sharif as a preacher started condemning the burning of the Koran by American soldiers in at the Bagram air base a few months before our visit. While we were made to feel very welcome and people were very friendly to us, it became obvious that not everyone would appreciate us being there.

Despite the cultural and lingual barriers, we got on really well with our bodyguards. They loved trying to stand on the skateboards with their guns over their shoulders. Every morning, the commander ‘Muydien’ would greet me outside the hotel, calling “brodar!” (Brother). He also loved holding my hand, which is supposedly pretty common in Afghanistan. But what can you do if a man holding a loaded weapon wants to hold your hand? A perfect example of our polar backgrounds came when I asked if he could use email. He replied – “My Kalashnikov is my internet”.

On our last day in Mazar-e-Sharif, were finally invited to meet Atta Noor. The ethnic Tajik was a high school teacher until the Soviet invasion, when he became a mujahideen resistance commander. He fought again in the late 90s against the Taliban alongside the ‘Lion of Panjshir’, Ahmad Shah Massoud. We were invited into his palace to drink tea and have a chat. We sat timidly in front of a TV camera nibbling biscuits, discussing the opening of a skate park in the Balkh province though the charity ‘skateistan’ in Kabul, before going outside to give a skate demo for everyone.

We left Mazar-e-Sharif on an internal flight to Kabul. The first worry was surviving the flight as the airport looked like a building site and the plane was at least 20 years old. The second worry was the unknown waiting for us in Kabul. No more protection or guards. We had a connection with Skateistan and luckily they agreed to put us up at short notice.

Kabul gave the impression of being a lot more open. It struck me in the Balk province that I hadn’t seen as much as a woman’s eyes during the four days we were there, whereas it seemed common in Kabul to see a woman without a burka. The streets were a lot busier and there was a much bigger foreign military presence. Many of the buildings were bombed out with walls full of bullets. The airport was bustling with thick-necked American GIs and I even saw a McDonalds wrapper in the car park. There were also a lot more foreigners working as NGOs or journalists.

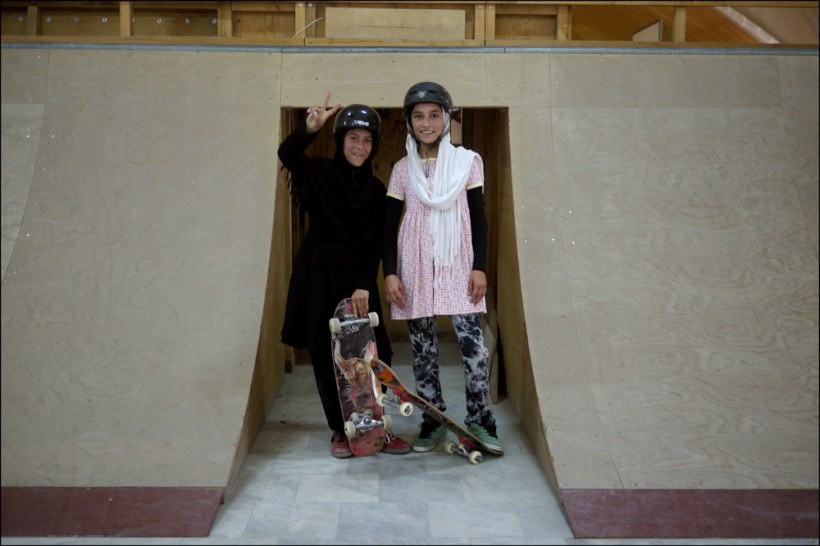

Skateistan’s founder, Oliver Perkovich, picked us up from Kabul airport. His project started out as simple skate classes in an abandoned fountain in Kabul city centre, but now there is a huge warehouse, filled with professionally made ramps on a marble floor. There are around 350 regular students and around 40% are female. Most of the students are illiterate as they have missed school to work on the streets, but a few of the kids have even started working for the organisation as skate instructors and I was surprised how quickly they have progressed in the short time they have been skating. Their English level was far beyond that of most adults we met in Afghanistan and they were incredibly confident, outgoing and sincere. The idea that anyone would want to harm these kids is unbelievable.

There were so many new experiences on this trip and it really opened up my eyes to how much I take for granted in my life and made me worry a lot about the future. Has the war in Afghanistan actually achieved anything? As international forces prepare to withdraw all troops by 2014, can we be optimistic about the future of Afghanistan? It’s not even worth mentioning what I might worry about on a daily basis in comparison to others living in fear that their bread-winning children could be blown up by religious fanatics while out selling scarves on the street for pittance. We are so lucky!