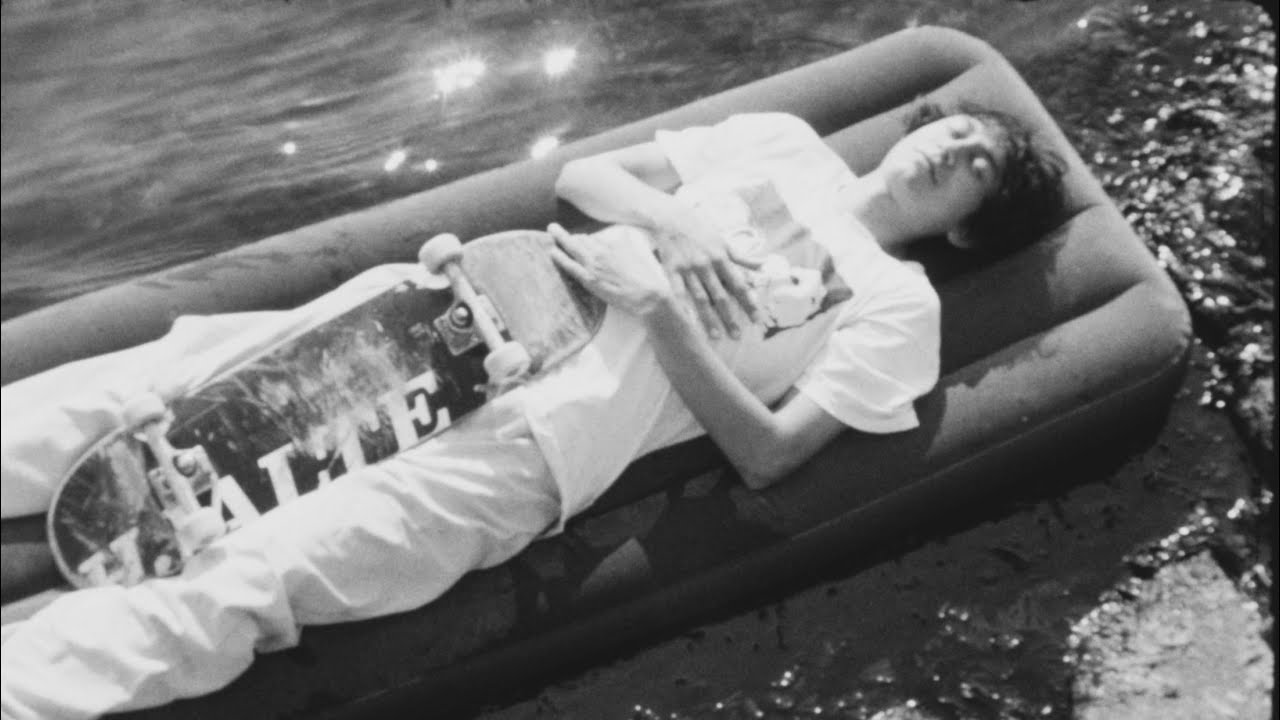

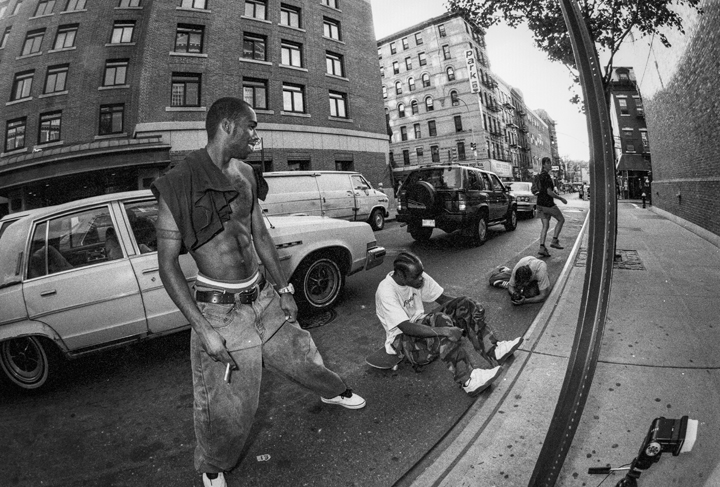

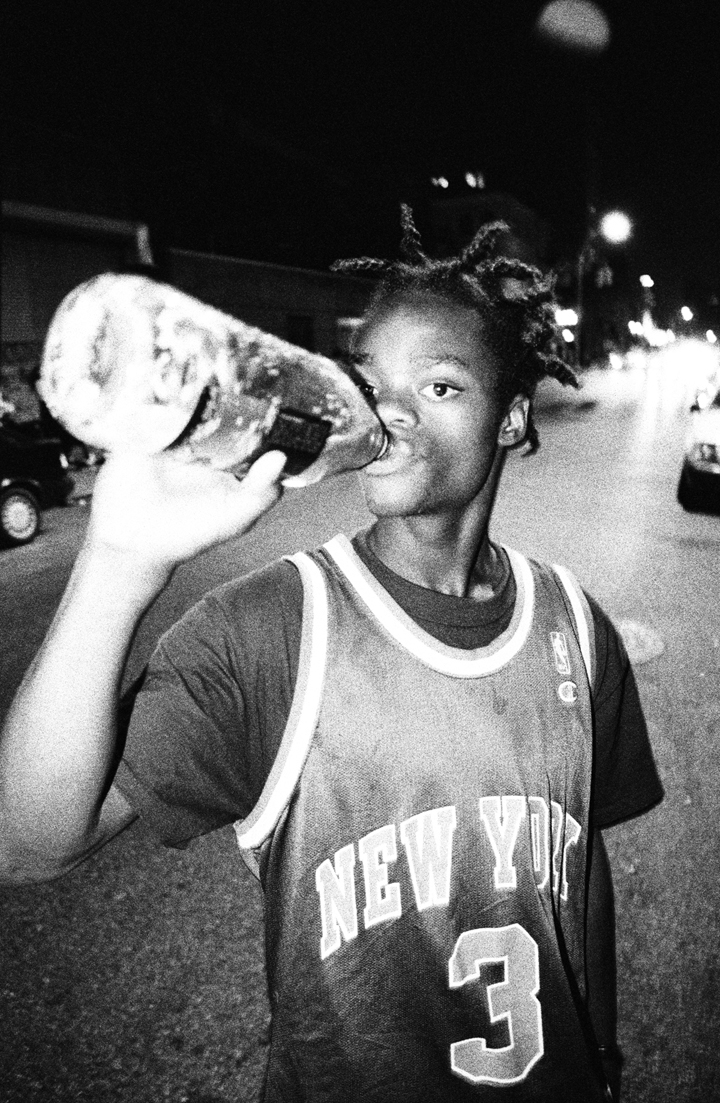

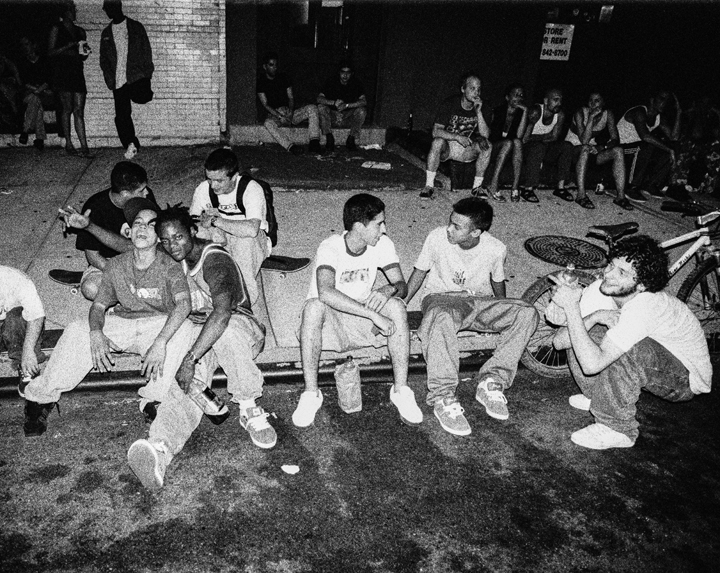

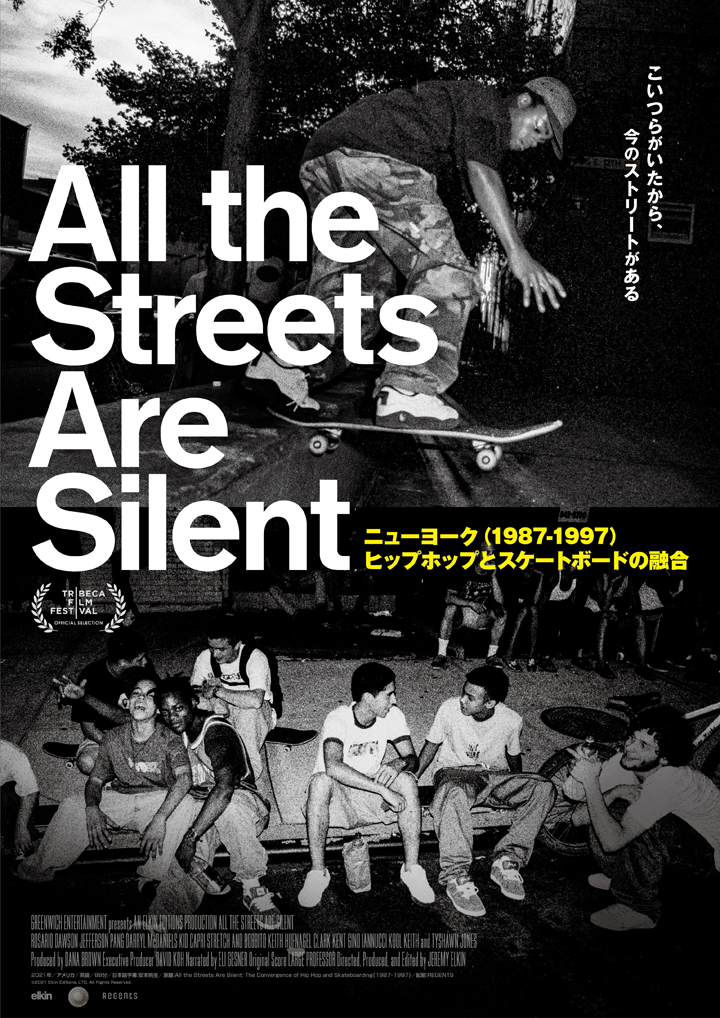

All the Streets Are Silent is a documentary film about the convergence of Hip-Hop and skateboarding. This is a love letter from Jeremy Elkin to the golden decade of New York.

──JEREMY ELKIN (ENGLISH)

[ JAPANESE / ENGLISH ]

Portrait_Zander Takemoto

Special thanks_Regents

VHSMAG (V): You're from Montreal and have been working on skate videos. How did you get into filming in the first place?

Jeremy Elkin (J): I grew up with three older siblings. One of my sisters always had photo cameras around. My brother was a skater in the eighties and a DJ and he would always come down to New York. So I always had that connection. My mom was from the Bronx, so it was always a pull to New York to see family or whatever. Moving to New York in 2009 - 2010 was pretty natural but I had already been here a million times. But how do I get into it? I think how anyone gets into it. It becomes really clear really quickly that the kids that you're skating with when you're 13 are way better than you. And even though I could fully skate, I wasn't hard flipping over a bench or something at 14. No one really had cameras in Montreal. There were two or three people downtown that had cameras. So I thought it would be a smart idea to start documenting it. And then one thing leads to the next and you've made a number of skate videos and a fun historical tool to look back on and have that memory captured at that time.

V: You started making skate videos in Montreal filming your buddies and stuff at first. And you said your mom is from New York but when was the first time that you got exposed to the New York skate community?

J: I was in Supreme when I was probably nine or 10. I was going there to get a shirt. I go back to Montreal and I remember friends were like, "Why are you repping a New York skate shirt?" It's so weird. I always loved the whole vibe of Supreme walking in. It was so different, such a different skate shop. I loved the New York scene. I always thought the New York scene was the sickest. I thought New York was a shinier Montreal. And now I appreciate Montreal in a whole different way. Having lived here now for 13 years, I think I love the Montreal scene. I think it's the best, but it's funny how things change as you get older.

V: You've made Lo-Def, Elephant Direct and The Brodies video series. How did all those skate videos happen? How did you end up filming New York skaters?

J: It's complicated. I'll tell you about that transitional period. I had made a number of Montreal videos and all of my videos dating back to when I was a kid had New York in them. We would always go to New York for a month. My brother lived over here on 12th street at the time and we'd crash at his place or a friend's place. Pryce Holmes worked at Supreme and we would stay at his place in Brooklyn when I was 19 or 18, however old I was. This is in the early 2000's. Back then we would go film at Flushing Meadows or something. We'd come back and plug in the VX or we'd burn a DVD of tricks we got and they would play it on the window at Supreme. I started coming down here so much and I was like, "My God, I'm spending so much a year on trains, buses, plane tickets, whatever, just to get here." I was like, I should just be paying rent or something. Since my mom was from here I had a US passport, so I didn't need a visa. It was a natural thing to finish Elephant Direct and then move down here. We did an East Coast trip where we were in New York for a few weeks, and went to Boston with a van full of skaters. Torey Goodall was on that trip and I remember he stayed in New York to party. That's the trip he met Lev and they started Palace. It's a small world. Everyone is friends, it's all a community. Everything is connected.

V: How did the film All the Streets Are Silent come about? Why did you decide to focus on the particular decade, 1987 to 1997?

J: I was born in '87 and my siblings are much older than me. They were in their teens when I was born. But my bedroom was across the hall from my brother's room and he was a DJ and a skater. I had a Beastie Boys and KRS-One poster before I could even speak, you know what I mean? I think it's the last great moment before 911, before the internet, before there was a big change like YouTube. And in having this archive from Yuki Watanabe, Eli Gesner and RB Umali, you get to relive it in a way and experience it. I was really honored to be able to even just see that footage, really privileged.

V: Most of the old New York skate footage came from Eli and he did the title for The Brodies. When I met him in New York, I remember him talking about a July 4th footage where Harmony Korine is kissing a girl. And fireworks are going off in the background... I think he was talking about using it for a music video. And I saw All the Streets Are Silent and it was the opening scene. That was beautiful.

J: I felt like it was too good to not open the film with it. It had to be just front and center, almost like its own artwork. That clip is so epic the way he shot it and everything, it had to live on its own. I didn't want it buried in the story, you what I mean?

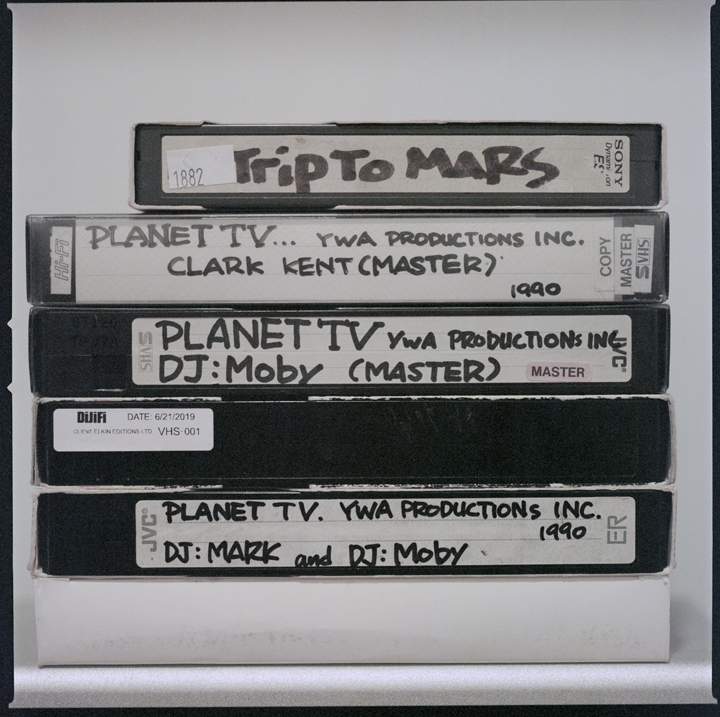

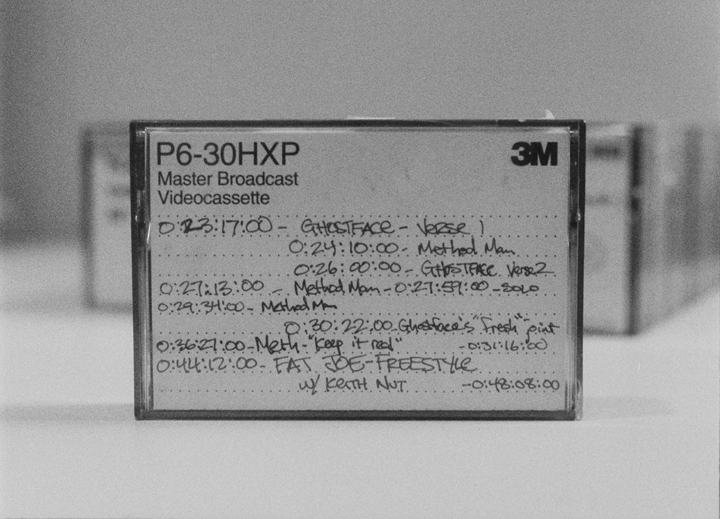

V: But how tough was it to digitize all the footage and decide which one will make it into the film? What was the process like?

J: It was an easy decision. I like to think of what I do as a bit of a curator. And my role is a bit of a historian curator with this documentary. If I get excited on a clip, the viewer's going to also be that excited. And if it didn't give me that feeling, it doesn't go in the film. Another thing is that there were also clips that couldn't go in the film. Let's say it's a clip of Gino Iannucci, there's an amazing clip of him we didn't use. He switched pop shove-it over a garbage can. No one's ever seen it and it's never come out. It was on a tape that Peter Bici filmed at Aster Place and it's really dark. Because it's four by three, Gino goes out of frame to where it's just his wheels in the shot and it's the garbage can. Certain clips I really held near and dear to my heart that were like, "My God, I can't believe I'm getting to see this clip." I didn't use it because it just didn't fit.

V: You've witnessed all the gems.

J: Definitely. Eli had some amazing footage, same thing with RB. I think Yuki also... I only went through about a third or less of Yuki's tapes.

V: Beside the footage that you got from Eli, can you talk about the other footage that you got from Yuki and RB?

J: RB is from Texas and I think he moved to New York about a year before Mixtape came out. Because the story is about '87 to '97, the last year is primarily RB's footage because Eli was at that point so busy with Zoo York. I think RB was the one in the streets pushing around with all the new guys like Anthony Correa and Danny Supa. Yuki on the other hand was filming every day for Mars back in the day. So when we get to Mars, there's footage of Eli's and if you really know what video footage looks like, Eli's footage has a look to it. It's a softer different camera. Each camera's got their own personality. So Eli's footage is probably, let's say five to 10% of that chunk of Mars. And then 90% of it is Yuki and Mayumi, his wife who films.

V: Filming everyday wasn't normal back then, was it?

J: It wasn't. He was way ahead. He would just film and stack tapes and he was labeling.

V: You've interviewed a bunch of people for the film. How many people did you interview?

J: I think 55 and it was 220 something shoot days for the film. And then we only used 33 or 34. There were about 20 that we didn't use.

V: Did you ever get intimidated by hip-hop artists?

J: It's an honor to even hang out. Asap Ferg was interviewed in the seat I'm sitting in right now. His interview wrapped and then I was like, "Dude, respect. Thank you so much for your time and everything." He's here with his bodyguard and his manager. And Ferg is like, "I'm not going anywhere." What do you mean? "I'm not leaving until... I want to hear your system." And he was just kickin' it, hanging out for so long. A lot of these guys they're such good people. They're so down to earth, so chill. So I wasn't intimidated. Is there someone from the film you want to know a story about?

V: Personally, Tek and Lil Dap.

J: Tek and Lil Dap are really close friends with Vinny Ponte. So, they're homies with Vinny and that's how that happened with those two. They go way, way back. Crazy. New York is so crazy. So I needed people to help me digitize tapes and I had a few homies come. There was this young girl and she was helping me organize and digitize tapes. She got to be there for the Bobbito interview and she was super psyched. And I'm on the phone with someone and we're talking about DJ Premier and getting a clearance. And she's like, "I could help you with that. My friend knows Premier." She's a little cute blonde girl. You don't think of a rapper or you don't make the connection. It turns out one of her close friends is Guru's son. So fast forward to the next day, Guru's son is in my apartment.

V: What?

J: And we're hanging out. He was really young. He was probably 18 or 19. Guru died in 2010. It's even weirder because they talked the same, they looked the same and they have the same name, Keith Elam. Keith actually helped us with some of the Premier clearances and his dad's stuff for the movie. So, we were able to use a clip of Eli and Bobbito or Mike Hernandez in a car. And there's a Guru track playing with a Premier beat. We were able to clear that because of Guru's son. That's insane. Really weird New York moment.

V: What about Lil Dap?

J: Lil Dap showed up, got out of his car with his manager who's his nephew and we were going to go to Union Square. But the week before, we shot Jeff Pang in Washington Square and we got a ticket for 400 bucks or something. I was like, "My God, I don't want another ticket." So we actually wound up going on a side street where I get breakfast all the time. That building's actually completely demolished where we shot him. But he was sitting on his little standpipe. It's a smoke pipe and he is just sitting there and we're getting ready to start the interview and he goes, "I need a minute." And we're like, "All right, what's up?" He's wearing a brand new gray Fila tracksuit. And he's got these brand new leather Filas on with the red and blue on the side. And he's like, "Yo nephew." And his nephew comes up to him with a box. And he walked probably one block and he was like, "Nah, I need the fresh kicks." And he swapped out his brand new Filas for another identical pair. He needs to keep himself fresh all the time.

V: Wow.

J: A lot of those guys... like Kid Capri with his watch. He needed 10 minutes to pick the watch. Ferg showed up with green leather shorts on and brand new everything. During the interview they have to feel like a million dollars. Brand new everything.

V: Were there any skater or hip-hop artists that you wish you had interviewed for the film?

J: We almost got Fat Joe. Busta Rhymes is another one I wish was in there, but he did a similar interview for Stretch and Bobbito doc. So I get it. It's maybe actually better that he wasn't in it because of the way Stretch talks about it. It's not in the final film but Bobbito had an amazing quote about Busta. He said he was shitting himself when Busta was performing. The reactions sometimes are better from the outside perspective. Because Busta, what's he going to say? "I just came up there and rapped and left."

V: I saw a clip of Kool Keith at one of your premieres giving you respect.

J: Kool Keith came to four premieres. The main premiere was 400 people, big theater. Everybody was there. And 20 minutes into the film, right before Kool Keith is on the screen, Kool Keith walks in with the Ultramagnetics. And one of my homies who was in the audience was like, "Dude, how did..." He's like, "Kool Keith is on the screen and he's walking by me to get a seat. How did that even happen?" So Kool Keith missed the first 20 minutes. Then the next night he comes and he missed the first 10 minutes. And at the end of the second premiere, he's like, "I got to come again." And the third night I showed up because we're doing a Q&A after and I was going to introduce the film. So I showed up and I went downstairs, Kool Keith is the first person in line to go see it. I'm like, dude you don't need to see this again. And then he came again. He came four nights in a row.

V: That's amazing.

J: So crazy. But the clip that you saw is from that night when he was waiting and was so psyched to see it fully, beginning to end.

V: Did you ever feel the pressure since you're not from the decade that your film features?

J: For sure. When we went to Stretch's place to do the interview, he was in his living room watching a rough cut of Mars, which was basically the only part he really wanted to see. He was like, "Do whatever you want, but you've got to get Mars right." Because Stretch came in at the end of Mars. So when Mars was closing, Stretch started to be a household name, maybe the last six months or something. It was at the end, the last window of Mars. And that's when he met Bobbito and then he wound up doing the radio show. Stretch was really concerned about a dialogue quote matching a certain visual from Mars and making sure it locked and everything was factual. So we met back and forth a lot on that and he had some great feedback. If Bobbito's talking about the roof, the stairwell that we show going up to the roof is the stairwell going up to the roof. Stretch wanted to make sure every clip was specific.

V: Yes, that tells that your film is super factual and is true to what really happened. It's nice that we get to relive those days.

J: It's the last great decade before 911, before the internet took over, before social media, before et cetera, et cetera. Before the change. I think even just the change in cities, the architecture, whether it's a curb or a building, whatever it is. The building materials changed. Glass towers came in the 2000's. It's just a nice love letter to that final decade. When the 80's was ending and the 90's was starting, it was exciting. It's the era before the internet changed everything. New York became a really different place. You walk down the street and you can see how special those days were, when you have a girl listening to Wu-Tang Clan and a dad who's in his sixties wearing North Face, Supreme or whatever. I think they all reminisce about that time because it was magical.

V: Your film means a lot to the skaters who were into the New York scene and I can assume the same for hip-hop fans. It was a golden era for a lot of people from that generation...

J: If you like the New York scene, I think it answers a lot of questions. It just pieces together so many stories into one narrative. That was the goal of it. I think the Stretch and Bobbito documentary was amazing. There's been Deathbowl to Downtown and it's a great skate documentary. There've been Vice specials later, but they don't kind of connect everything in that same way. I wanted to make something that had more of that connected tissue, tying all these stories together through one central narration. And also including people that are new perspectives, new voices that weren't in those other stories because there's usually the same group of people interviewed over and over again. I just wanted to be a little fresher and hear perspectives from the people who don't normally go on camera. Gino, Kalis, Carroll, Pang from the skate community. And then there's Tek, Black Sheep's in there, Clark Kent, Stretch and Bobbito... Large Pro on the soundtrack. These are people who don't give full interviews usually. It would've been cool to get some of the bigger name hip-hop heads, but at the same time, it's nice that it was really underground. Just the right people who need to be in it and that's it. It was a journey.

Jeremy Elkin

@jeremyelkin

Born in Montreal, Canada. He has produced various works from skate videos to documentary films such as Lo-Def, Elephant Direct and The Brodies.

For theater information, check out the official site of All the Streets Are Silent: https://atsas.jp/