Over a decade since stepping away from skateboarding, former skate photographer Pete Thompson comes back with a book that captures his journey through skating from the early '90s to the early '00s. Let's take a look back on his career that started in '93 along with some of his historical photos.

──PETE THOMPSON (ENGLISH)

[ JAPANESE / ENGLISH ]

Photos courtesy of Pete Thompson

VHSMAG(以下V): Congratulations on your book. You had photos from the '80s in the introduction of the book; when did you start shooting photos?

Pete Thompson (P): I feel like I was taking photos when I was around 10 but I was just shooting with a point and shoot camera. It was a Konica that my grandmother bought me. I took the camera everywhere with me but I wasn't trying to be a photographer. I just took photos of things that were around me and not necessarily even skateboarding all the time. So that's how it started. I'd say from '86 up to '91, it was just point and shoot camera. And then in '90, I got a SLR, which was a Ricoh. So when I got that camera that was when the photos started to be more Intentional. But the point and shoot camera was what I had with me at the first year of the YMCA Santa Clara Skate Camp.

V: That's in '88, those photos are in your book.

P: Yeah. That's the summer when H-Street started. At the camp, I got to see Matt Hensley, Brian Lotti, Ron Allen, Ray Barbee, Carl Hyndman... So the photos of Danny Way and Neil Blender are from that skate camp.

V: Danny Way was still riding a Vision board.

P: Yeah. I'd never heard of Danny Way, but that's all the pros were talking about. I was like, who is Danny Way? But I was on the deck with my little point and shoot camera taking photos and I'm really lucky that I still have some of those photos.

V: Aren't you from North Carolina? Did you fly over to California for that skate camp?

P: Actually I lived in Northern California until I was 12 and my family moved to North Carolina. I was skating in California before we moved to North Carolina. I lived in North Carolina for 12 years and that's where most of the skate photography began and really started to take shape.

V: What was it like back in '90 when you started shooting more intentionally?

P: I don't know if skateboarders today can really understand what that whole experience was like. When a magazine came out, you stopped everything you were doing, sat down and read the magazine cover to cover four times. You wanted to see what was happening, what was cool, what tricks people were doing. Everything was changing so quickly. If you weren't living in California at that time as a skateboarder, you were living in the wilderness. So when I looked at skate magazines, it was like a fantasy world that you're having a peek into. I loved the still moments and the curiosity that your mind would conjure up looking at these still shots. I would wonder, "What was this day like? What was happening before and after this picture was taken?" The perfect moments were printed in a magazine. It's a really beautiful moment to look at and absorb in a way that really connected with me.

V: Who were your influences back then?

P: Grant Brittain, Spike Jones, Dan Sturt... I loved their photos for different reasons but Dan Sturt was probably the biggest influence. Looking back, I realized that the form of skate photos was being redefined. Skateboarding can be rigid in terms of how you photograph it. In a sense, everybody follows this one rule that is sort of unspoken. You have to show where the skater is taking off from, what the skater's doing in the middle of the trick and where they're landing. And there's nothing wrong with that. It's a measurement. You're quantifying what's happening in the picture so that the reader can get a clear idea of how to place this trick amongst all the other tricks that have come before it. I think with Dan Sturt, he broke the form. From my perspective, he said, "Let's just stop. I'm going to show you something that maybe you haven't seen before." Not in the sense of what the trick was, but in the sense of his gaze and what he was communicating from the standpoint of lighting, mood and the way that you would feel when you looked at the picture. With skate photography, you feel something when you look at every picture and it's usually like, "Oh, that's a sick trick." Or, "That makes me want to skate." But I think Sturt dug a little bit deeper into the unconscious mind.

V: So you're in North Carolina and you started working for Slap. How did that happen?

P: I was around a lot of great skateboarders in the beginning of their careers, because I was skating the whole time. I was a flow on Dogtown. So I was at a skate contest in North Carolina and all these guys from Washington DC were there. Lance Dawes was skating in the contest and I remember talking with him. I think it was right before he started working at Thrasher and ended up doing Slap. So when he started doing Slap, I think I sent him photos. It took a little while for Lance to actually run a photo of mine. He was really helpful in those early years.

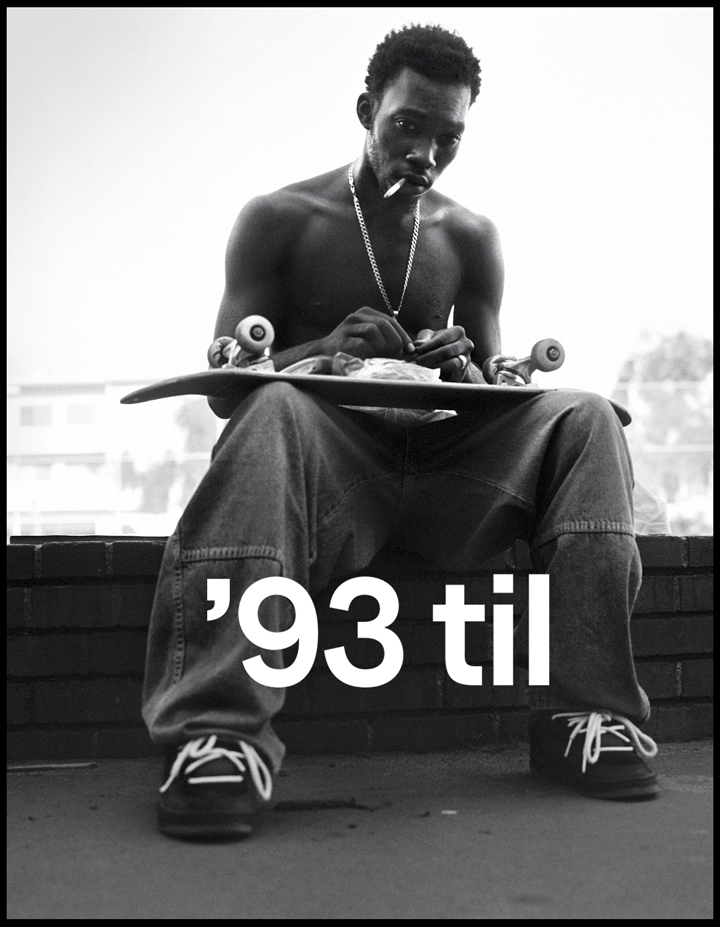

'93 til cover - Stevie Williams - San Francisco 1999

V: By looking at the title of your book, the year '93 must have meant a lot to you.

P: '93 was the year I got my first photo in Slap. I think it was a photo of Mike Sinclair. Out of focus, blurry, terrible... terrible photo (laughs). And then a photo of Daniel Powell who was an amateur for Underworld Element in Atlanta. That ran as an ad for Underworld Element. It's also obviously the title of the song by Souls of Mischief. I thought I would shoot skateboarding forever when I was 21. So there's that open-endedness to the title. You really never know where this art form is going to lead you.

V: What was the reason for having Stevie Williams for the cover?

P: First off, as soon as I decided I was going to do a book, I thought the cover couldn't be a photo of somebody skating. That being said, it makes it difficult to choose the photo. Who are you going to pick and how will people know that this is a book about skateboarding if the guy's not skating? And what's going to be something that really encompasses my feeling about photography, which is, simple, straightforward, black and white portraits that are lit naturally. I think that the idea of picking Stevie was this picture had all those things and his journey is such a remarkable sequence of events. He's got the board, rolling a joint and glancing up at the camera. That's how he was when I asked him to shoot portraits. He was like, "Yeah, go ahead.” Like, I'm not going to do anything different. I'm just going to keep doing what I'm doing. I didn't realize it at the time, but that's the dream when you're shooting a portrait of somebody. They're going to be themselves and not try to pose or do something cool.

V: In your book, you wrote that your career started in Washington DC. Did you ever get vibed? What was it like there?

P: I think my experience of meeting and spending time with those guys at Pulaski and DC was probably much different than your average kid. I would go up there with friends from North Carolina, and because I knew Lance Dawes... it wasn't like we were instantly part of their crew, but we were welcomed in. Also by that time, my photography was at least getting to the point where it was somewhat consistent. DC was the closest big city from North Carolina that had street skateable terrain. But those guys were all super cool to me. I mean, I know that you would get vibed there if you didn't know anybody. And that's how it was, no matter what city you're in. It wasn't pretty. You literally had to be able to keep your cool and keep your head down and skate. Or just be really funny. If you were really funny and you were part of the crew, that was it, you were in, you know what I mean?

Andy Stone - Washington DC 1994

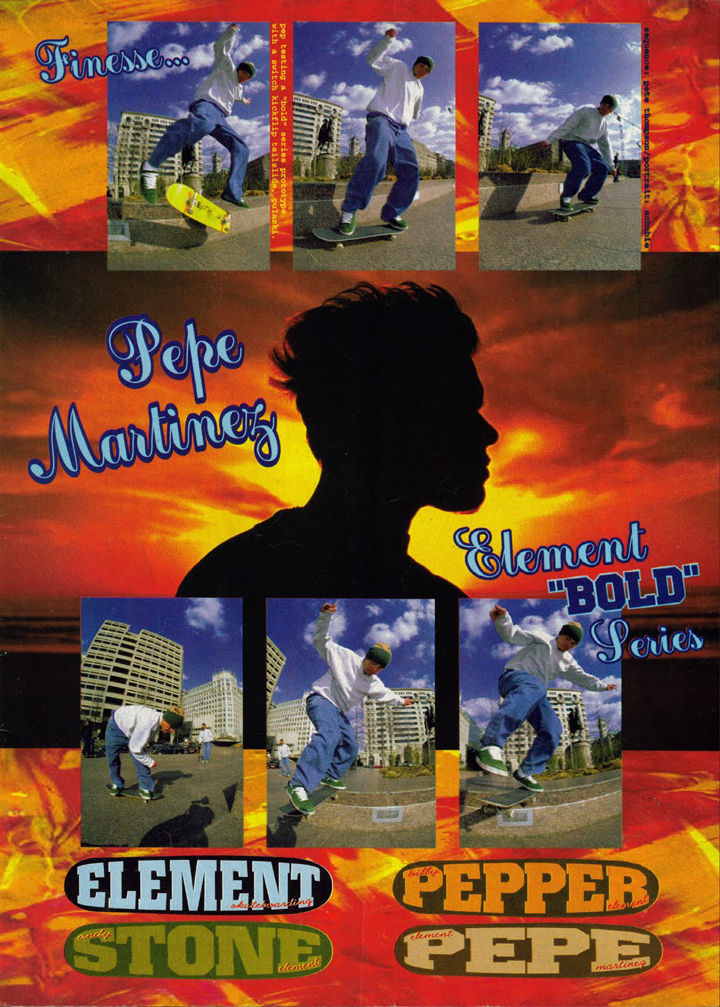

Pepe Martinez - Washington DC 1993

V: What was Pepe Martinez like? I can't recall any interview of him and I've only seen his photos and footage.

P: He was a pretty quiet guy. He was an observer who wasn't that talkative. But when he did talk he was super funny. He would just crack jokes. I mean, he was a really, really good friend to that crew of guys in DC at the time. He knew his talent level was above and beyond everybody that was around. He knew how good he was but he was so humble. He was adored by everyone around him. He had a lot of dignity and a lot of class. And if you mix all that with his skating, it's easy to see why people have such an undying love for the guy. Sensitive, compassionate and fucking amazing skateboarder. He was probably the first color sequence I ever shot, a switch backside kickflip tailslide at Pulaski. It was an Element ad. I shot maybe four or five rolls, and that was on my last roll. He bails and picks up his board and I'm squatting on the ground. And as he's picking up his board, I was like, "Dude, I got one more left." And he's like, "Alright, I got this." And he goes back, turns around, pushes towards the ledge. Does it perfectly and rides away.

Pepe Martinez Underworld Element ad - Washington DC 1994

Jamie Thomas - Atlanta 1994

Ronnie Creager- Venice Beach 1994

V: How about Tom Penny? You have a lot of him in your book.

P: Yeah. That was the right place, right time. I went to Europe in '95 for the first time. That was for Transworld. I started working for Transworld in '95.

V: Isn't that kind of like a rare move, going to the rival skate magazine?

P: Yeah. That was pretty ugly... it got a little messy. It was interesting to me because I was just some kid on the East Coast. I didn't think that anybody at Thrasher knew who I was or cared what I was doing. I didn't think I was on their radar at all. So when I left, it was a big deal for some people. And I, being a 20 year old kid, this is a huge deal. It was like my entire world was going to collapse. But going to Transworld really opened up a lot of opportunities for me. I mean, within five months I went to Europe.

Andrew Reynolds - Copenhagen 1995

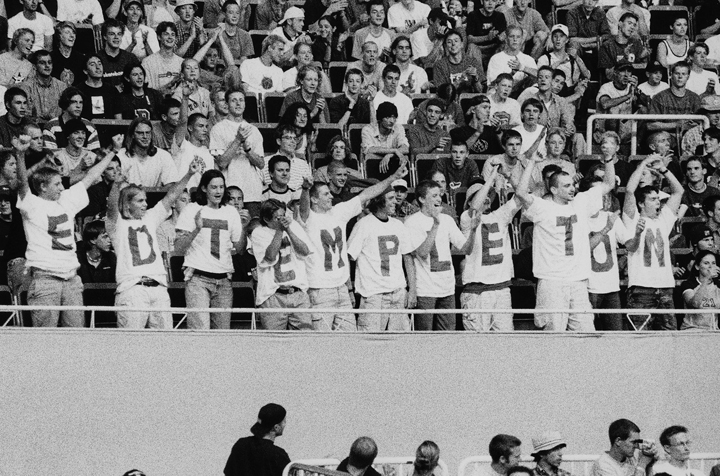

Titus World Cup Templeton Fans - Munster Germany 1995

V: And you got a good amount of Tom Penny.

P: Yeah. That's what I mean by right place, right time. I was super lucky just to be there. And then also just to be in the van after the contests with Penny, Reynolds, Matt Beach...

V: I saw the video you made, the one Tom Penny is sleeping in the van. You were filming as well?

P: Yeah, that was kind of how it went. The importance of the quality of a video part hadn't quite gelled yet. Stacy Peralta did it with the Bones Brigade, but that's a completely different era. It worked until guys like Dan Wolfe came along and took it up 10 notches. Also if there was a filmer, the skaters didn't have to do shit twice.

Satva Leung - San Francisco 1997

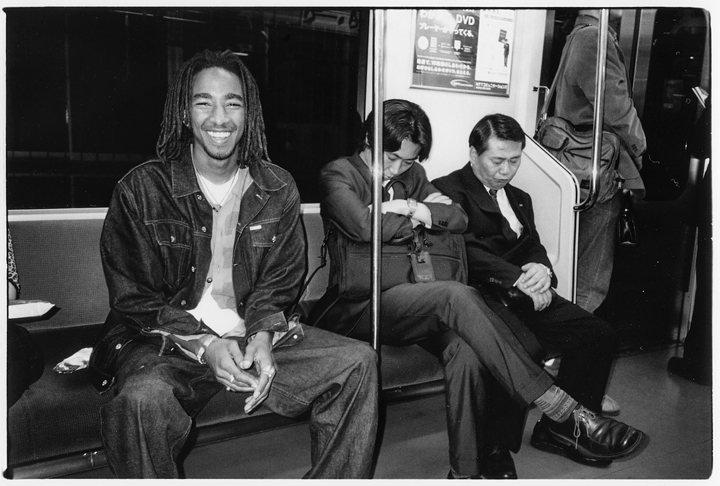

Danny Gonzalez - Tokyo 1999

V: I heard that film shifted to digital around when you were leaving skateboarding in 2004. It must have made things easier for a skate photographer. Why did you leave at that time?

P: Well, me leaving at that time had nothing to do with digital. For sequences, that was obviously an advantage. Actually I won't even call it an advantage. I'd call it a convenience. But by that time in my career, if I shot sequences or stills, I was pretty confident that everything would come out. Had digital come along in '94, that would have been the most amazing thing that ever happened in my career (laughs).

Karl Watson - Tokyo 2001

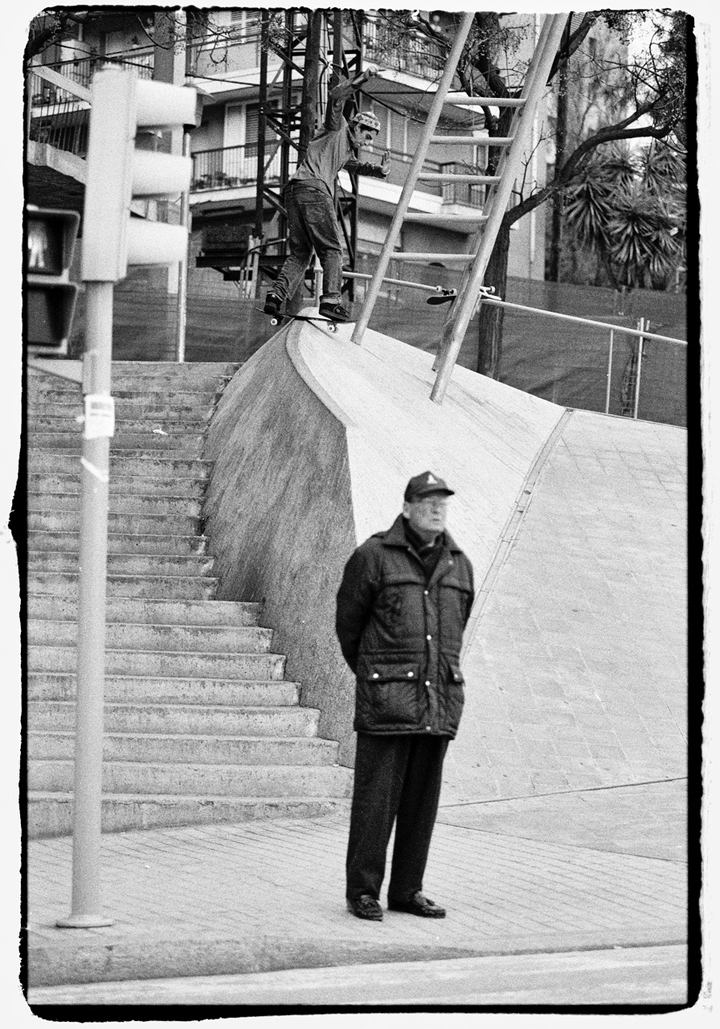

Kenny Reed - Barcelona 2003

Jack Curtin - Miami 2004

V: Do you think shooting film was very important to form your creativity in photography?

P: Yeah. It slows you down because you have to be more mindful, more plotting and actually think about what you're doing. And once you slow down, there's a lot of creativity that can start to gel and solidify. You have time to think about what it is that you're trying to show people. But it would have been great, being able to shoot high speed sync flashes. But I think that my feeling about leaving at that time was more based on just really feeling like I was doing the same thing over and over again. I wasn't moving in any direction creatively, which is a really frustrating place to be. And the nature of skateboard photography can be quite limiting. You have the fisheye from the bottom of the stairs shots that everybody is accustomed to. I just needed to do something different, and I couldn't continue to shoot skateboarding and do something different at the same time. I don't know if I actually consciously knew this at the time, but I needed to end what I was doing in skateboarding and have a clear space for other things to sort of trickle in. So I just had to get out completely. I had a lot of things that I wanted to say with photography that I was unaware of. I knew I had it. I knew I had that desire to do something but I didn't know what it was, which is an even bigger reason for taking skateboarding out of my life completely. When you're trying to figure out what you want to do creatively, that's the time to empty your mind and just experience and absorb new things.

V: So what do you do now?

P: Mostly portraits, commercial advertising and lifestyle. I think that every artist has a dream of being a specific type of artist. You have this idea of the art that you like and then there's the art that you're capable of creating. Those two things are not always aligned with one another. So I think over time I've learned what kind of photography I'm good at, and what type of photography I can appreciate when I see other people do it but I personally am not good at. I think that's a big part of the journey of an artist, to try to have that conversation and figure that part out. So I enjoy the stuff that I do. I enjoy raw unguarded authentic moments that really show someone's true colors. And then sort of putting that in the context of advertising and all these other applications.

V: What was the transition like? Did you ever go through struggle in the real world?

P: Oh my God. I was basically broke for 10 years. It's funny because when I started working on the book, I heard somebody say that there were people who said that I was a sellout back then (laughs). I thought to myself, "Sellout? What did I sell out? I ate ramen noodles for eight years." I was fucking broke. I did whatever I had to do. I shot weddings. Which, by the way, is a really, really good exercise if you want to understand photography. Creatively, not so much... But if you want to understand technical photography and do it quickly and be efficient, then shooting weddings actually is a good exercise. And then the other part that was really helpful was being a first assistant for four years. But I also think the struggle I went through was an identity struggle. I started skating when I was 10, so my whole identity and worldview is shaped by skateboarding. Looking back, skateboarding has put this deep stamp on how I see creativity for the rest of my life. That's the best part of skateboarding. Having that experience is priceless. And when you look at creativity in the context of skateboarding, there are no wrong answers. Nobody can tell you that you're doing something wrong. It's the same thing with photography.

V: It's subjective.

P: It's absolutely subjective. It has to do with something that is deeply rooted in taste. And taste is so important when it comes to being an artist. I think that with skateboarding, skateboarders develop taste over time in the same way an artist does. It changes. It evolves. So when you talk about what I got from skateboarding and what I still carry with me, that's it. That idea of there's no wrong answers. And that frees you to be able to do whatever it is that makes you feel alive. Whether you're rolling down the street doing a 360 flip or taking a photo.

V: After being away from skateboarding for over a decade, what inspired you to make this book?

P: I don't know if inspired is the right word, but what really struck me about this entire archive collection of pictures was that my view of it had changed. I don't know how I could have ever done this had I kept shooting skating, because in your mind what you've created has a certain worth to you and everybody else that you carry with you. And if you can somehow step away from that mindset, you may be able to see your photos in a different light, maybe see your pictures from the perspective of another person's eyes who doesn't skate. That was the main thing, was I wanted the pictures to obviously be appealing to skateboarders, but I also wanted people who don't skate to be able to look at the book and be, "Wow, there's a lot of cool pictures in here." So you have to detach yourself from the pictures that you have been told your entire career as a skate photographer are the good pictures.

V: I see.

P: It's like Pavlovian. You're going to keep hitting that same lever to get the same response, because it feels good. But when I started to look at these photos and see them differently, I felt like I was in a place where I could put a body of work together, put it out there and inspire people in a way that wasn't based on any accolade or approval from past skate magazines. I know people want to see pictures of Tom Penny. But at the same time, I don't necessarily want to show a bunch of Tom's photos that have already been seen unless you can show them from a slightly different perspective. For example, the back cover is a photo of Tom that's from a sequence. The main goal of the book is to show people something new, and try to expand their scope of understanding of that time period and photography. Because for me, making the book is no longer about the sickest skate photo.

V: Did you select some of the photos based on your emotion?

P: Definitely. I think it's a level of softness and sentimentality that has allowed me to look back at these pictures with affection rather than like, "I need to get away from this world and do something different," which that phase definitely happened. But in order to reconnect with my affection for skateboarding, that had to happen. And also to look at it from the context of just photography.

V: Is there any skater or photo that you wish you had that didn't make it in the book?

P: Definitely. When you're doing a book like this, it's so hard to choose what goes in and what doesn't. There's a lot of moments where I was like, "I want to use a photo of this guy. I only have a total of three photos of this guy but he's skating a spot that somebody else is skating. Or he's doing a trick that somebody else is doing. Or the quality of the image isn't that great. Or it was already published." So it's either I didn't have the right picture of them, or the picture that I did have of them had already been published. I mean, there's published photos in the book, but you want to keep as many unseen photos as possible for a project like this. Also there are guys that I spent a lot of time shooting with that I really wish I had a portrait of. It's so difficult to arrange all of those pictures in a way that fits together. I really would have loved to have a photo of Jose Rojo, Rob G., Ricky Oyola and so on...

V: Ricky Oyola photo would have been great.

P: I have one photo of Ricky that I might end up using for the next book, because I'm going to do another book. It's hard because if I had a color photo of Jose Rojo that was shot with fisheye, I probably wouldn't use it. Because fisheye from below with flashes, it's great to show skateboarding as a contemporary thing in the moment, but in terms of its longevity, those types of images aren't timeless for me.

V: The book has four sections. Early '90s, mid '90s, late '90s and early 2000s. Which era is your favorite?

P: I can't say, but I almost feel like the pre-section is the best, the Neil Blender, Danny Way. I was not even a photographer yet and having those pictures is just sheer luck. Not to take away from the other chapters but it's a process, there's technically shitty photos or damaged photos. And some of them, I didn't even have negatives for. Like the photo of Wade Speyer, it's a print and I had to scan it. Same with Ed Templeton and Geoff Rowley portrait. I don't have the negative.

V: Anything you miss from those days?

P: The one thing that's really amazing about being a skateboard photographer is there's nobody over your shoulder telling you anything. You're out there doing whatever you want to do and that creative freedom is priceless. And the fact that you're around a bunch of guys that do exactly what they want to do with every minute that they have. They love it and they do it for reasons that usually have nothing to do with anything except just your own desire to push yourself and see what you're capable of. Being around people who are super passionate is intoxicating.

V: Both skaters and people don't skate, how do you want them to feel when they look at your book?

P: I just want people to remember what it feels like to be 13 or 14. That feeling of those years and having something that you really want to put everything that you have into. If you have that, whether it's skateboarding or anything else, you're lucky. That feeling of that time is something that a lot of people look back on with a real sense of affection because life gets serious. You have friends that pass away. You have heartbreak, crisis and all of these things happen in life. There's uncorrupted purity to that time period.

Pete Thompson

@93til_skateboarding / petethompsonphoto.com

Pete shot for Slap and TWS in the '90s and left behind some of the most historical skate photos. He stepped away from skating in '04 to explore further possibilities as a photographer. '93 til, a compilation of archival skate photos, is now available in skate shops nationwide.